Sunday, 10 April 2011

Joseph Cornell: The Puppet Master

Surrealist artist turned film experimentalist, Joseph Cornell is perhaps most recognised for his assemblage art pieces, or simply, boxes. Cornell was widely celebrated for his innate ability to transform the ordinary and mundane in to something fantastical. Like a skilled puppeteer who can transform lifeless pieces of wood and cloth in to a young boy that can sing and dance, Cornell could transform plastic ice cubes in to rare jewells, balls in to planets, and small wooden boxes in to exubriant microcosms. It is from this platform that I began to speculate, and attempt to decipher, Cornell's first effort at translating his art form to the silver screen in Rose Hobart.

Given that Cornell's artworks required him to have a particular penchant for recycling discarded objects, it comes as no surprise that his efforts at film-making see him use a similar technique. The footage used in Rose Hobart is taken almost entirely from the 1931 B-grade jungle flick East of Borneo. Jeremy Heilman notes that Cornell's radical reappropriation of this film requires its viewers to "reassess the complexity of the images they see when they watch even the simplest of mainstream films." Indeed, this is exactly what Rose Hobart achieves, as it transfigures an easily digestible piece of cinematic pulp in to something far more existential and intellectually stimulating.

Through the process of removing all dialogue from the film, cutting virtually every scene that does not feature the all-but-faded Hollywood starlet, and coating the entire film in a dream-like blue wash; Rose Hobart becomes almost entirely seperate from East of Borneo, and thus completely submits itself to Cornell's control. In Cornell's manifestation of the film, Hobart's every movement, every glance, every breath seems to be subject to the puppet master's desire, and the result is highly rewarding. As one watches on, they are stripped of the choice to transfix their attention on anything else but Ms. Hobart, with the occassional exception of an errupting volcano, a slowly expanding ripple in the water, or a mesmerising solar eclipse. However, the wonder of Cornell's work is that these fleeting images do not divert any attention away from Rose Hobart, but rather, they intensify it, as she seems to be connected to, or even responsible for each of these natural wonders.

Such is the effect of Cornell's film that we the audience, like him, become utterly obsessed with this woman, as she is made to move, to smile, and even to breathe in a way that excites and entices us in our induced dream-like state. Hence, Cornell becomes the ultimate puppet master as he not only controls the movements, the reactions, and the emotions of his title subject, but by doing so, he manages to control the audience as well.

Tuesday, 5 April 2011

The Symbiosis of Man and Machine in Vertov's "Man With a Movie Camera"

"We call ourselves kinoks -- as opposed to "cinematographers," a herd of junkmen doing rather well peddling their rags."

This opening statement of Dziga Vertov's Kino-eye Manifesto makes no reservations in drawing a clearcut distinction between the 'commercially driven' directors of Hollywood, and Vertov's own 'truth seeking' group of cinema-eye men. Whilst denouncing the many misgivings of American cinema; the sweet embraces of the romance, the poison of the psychological novel, the clutches of the theatre of adultery; Vertov attests that the only way to preserve the pure art form of filmmaking is to purvey a truth that can only be achieved through the synergy of man and and machine, a filmmaker and his camera:

"I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it."

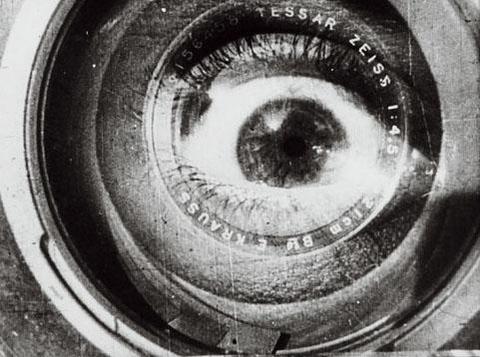

It is this concept of a fused life form between man and camera that consumed the majority of my attention when viewing "Man With a Movie Camera". From the opening scene in which a little man creeps out of a movie camera and begins to set up a second movie camera on top of it, we the audience are instantly transported to a surreal world in which man and machine share an intrinsic connection. Indeed, this somewhat kindred relationship continues to plague the entire film. From wide-panning long shots of industrial factories that suddenly transpire into images of new born babies, and then to mannequins (a by-product of man and machine); to the harmonious streams of trains and pedestrians that harmlessly dissect one another's paths; to the rapid cutscenes between a human eye and the industrial world it observes; to the rhythmic and all but autonomous movement of the mechanisms involved with mass production... the entire landscape of "Man With a Movie Camera" appears to be one giant testament to what can be achieved through the coalition of man and machine.

Whilst I am sure there is so much more to be taken from a film that many consider to be Vertov's magnum opus, I reluctantly admit that it was this relationship, and this relationship alone, that absorbed my conscious thought as I watched this film. As such, when I started to reflect on what I had seen, I began to speculate as to whether this film was so polarised from the American archetype of filmmaking that Vertov and his kinok colleagues so readily denounce, or whether it was in fact quite similar albeit for one predominant twist. The elaborate movement and tempo of the machines at work projected all kinds of theatrics, the gallant crusader that was the man with the movie camera provided, at least partially, some sense of narrative structure as he navigated and captured each part of his world from dawn till dusk, and, what I found to be most striking of all, the admiration and adoration of the mechanical world, and the subsequent union of man and machine certainly suggested to me some kind of perverted romance.

This opening statement of Dziga Vertov's Kino-eye Manifesto makes no reservations in drawing a clearcut distinction between the 'commercially driven' directors of Hollywood, and Vertov's own 'truth seeking' group of cinema-eye men. Whilst denouncing the many misgivings of American cinema; the sweet embraces of the romance, the poison of the psychological novel, the clutches of the theatre of adultery; Vertov attests that the only way to preserve the pure art form of filmmaking is to purvey a truth that can only be achieved through the synergy of man and and machine, a filmmaker and his camera:

"I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it."

It is this concept of a fused life form between man and camera that consumed the majority of my attention when viewing "Man With a Movie Camera". From the opening scene in which a little man creeps out of a movie camera and begins to set up a second movie camera on top of it, we the audience are instantly transported to a surreal world in which man and machine share an intrinsic connection. Indeed, this somewhat kindred relationship continues to plague the entire film. From wide-panning long shots of industrial factories that suddenly transpire into images of new born babies, and then to mannequins (a by-product of man and machine); to the harmonious streams of trains and pedestrians that harmlessly dissect one another's paths; to the rapid cutscenes between a human eye and the industrial world it observes; to the rhythmic and all but autonomous movement of the mechanisms involved with mass production... the entire landscape of "Man With a Movie Camera" appears to be one giant testament to what can be achieved through the coalition of man and machine.

Whilst I am sure there is so much more to be taken from a film that many consider to be Vertov's magnum opus, I reluctantly admit that it was this relationship, and this relationship alone, that absorbed my conscious thought as I watched this film. As such, when I started to reflect on what I had seen, I began to speculate as to whether this film was so polarised from the American archetype of filmmaking that Vertov and his kinok colleagues so readily denounce, or whether it was in fact quite similar albeit for one predominant twist. The elaborate movement and tempo of the machines at work projected all kinds of theatrics, the gallant crusader that was the man with the movie camera provided, at least partially, some sense of narrative structure as he navigated and captured each part of his world from dawn till dusk, and, what I found to be most striking of all, the admiration and adoration of the mechanical world, and the subsequent union of man and machine certainly suggested to me some kind of perverted romance.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)