"We call ourselves kinoks -- as opposed to "cinematographers," a herd of junkmen doing rather well peddling their rags."

This opening statement of Dziga Vertov's Kino-eye Manifesto makes no reservations in drawing a clearcut distinction between the 'commercially driven' directors of Hollywood, and Vertov's own 'truth seeking' group of cinema-eye men. Whilst denouncing the many misgivings of American cinema; the sweet embraces of the romance, the poison of the psychological novel, the clutches of the theatre of adultery; Vertov attests that the only way to preserve the pure art form of filmmaking is to purvey a truth that can only be achieved through the synergy of man and and machine, a filmmaker and his camera:

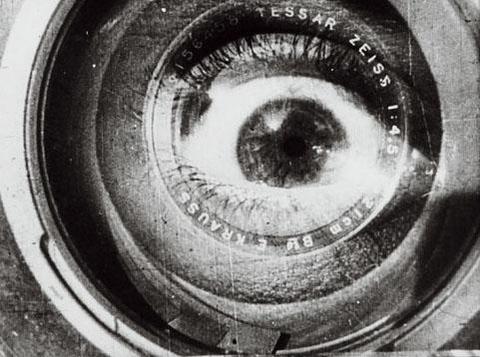

"I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it."

It is this concept of a fused life form between man and camera that consumed the majority of my attention when viewing "Man With a Movie Camera". From the opening scene in which a little man creeps out of a movie camera and begins to set up a second movie camera on top of it, we the audience are instantly transported to a surreal world in which man and machine share an intrinsic connection. Indeed, this somewhat kindred relationship continues to plague the entire film. From wide-panning long shots of industrial factories that suddenly transpire into images of new born babies, and then to mannequins (a by-product of man and machine); to the harmonious streams of trains and pedestrians that harmlessly dissect one another's paths; to the rapid cutscenes between a human eye and the industrial world it observes; to the rhythmic and all but autonomous movement of the mechanisms involved with mass production... the entire landscape of "Man With a Movie Camera" appears to be one giant testament to what can be achieved through the coalition of man and machine.

Whilst I am sure there is so much more to be taken from a film that many consider to be Vertov's magnum opus, I reluctantly admit that it was this relationship, and this relationship alone, that absorbed my conscious thought as I watched this film. As such, when I started to reflect on what I had seen, I began to speculate as to whether this film was so polarised from the American archetype of filmmaking that Vertov and his kinok colleagues so readily denounce, or whether it was in fact quite similar albeit for one predominant twist. The elaborate movement and tempo of the machines at work projected all kinds of theatrics, the gallant crusader that was the man with the movie camera provided, at least partially, some sense of narrative structure as he navigated and captured each part of his world from dawn till dusk, and, what I found to be most striking of all, the admiration and adoration of the mechanical world, and the subsequent union of man and machine certainly suggested to me some kind of perverted romance.

Hi Adam. No doubt Vertov had a machine fetish, as advertised in 'Kino.' The film boils with the kind of enthusiasm for a mechanized future that led directly via express rail link to the gas ovens of Auschwitz. WW2 turned our love affair with the machines to poison. Hence Blade Runner, Brazil, Terminator, Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and the Borg in Star Trek.

ReplyDeleteThat late C20th terror has been assimilated and homogenized by the purveyors of the new machines: the smooth, soft-edged devices of Apple, the touch-screen with its smiling icons. Words like 'iCloud' and 'cookies.' Yet we are invaded, integrated as never before. Not sliced or severed by the machines, but melted gently into them. The machinery has become invisible. Who knew?